“To be buried while alive is, beyond question, the most terrific of these extremes which has ever fallen to the lot of mere mortality.” — Edgar Allan Poe, “The Premature Burial.”

The fear of being shoveled six feet under while still breathing ranks fairly highly in the top ten list of Things People Least Want To Happen. Even worse is the idea of actually regaining consciousness afterward, with no one to call for help and no means of escape. This fear was very real in the days before modern medical practice and the invention of instruments capable of accurately detecting heartbeat (EKG or ECG) and brain activity (EEG). This long-held dread, coupled with of a number of scientific discoveries and highly class-based social conditions in the Victorian era, led to a “moral panic” of sorts that created “protective societies” for the dead and scenes of hysteria at pauper funerals. Let’s look at the process that allowed this panic to emerge.

Back in these Bad Old Days, the tools available to a physician — presuming one was available, that is — examining a patient for signs of life were:

- Listening and watching for breathing

- An ear to the chest to listen for a heartbeat

- Checking for a pulse

- Whether the patient was starting to smell bad following failure of the other tests

Given the potential for error, the opinion of the presiding physician wasn’t always considered the last word. Prior to the advent of modern mortuary practice, corpses generally were “laid out” and prepared for burial by family members. It wasn’t uncommon for relatives (often children) to take turns keeping watch over Grandma’s body while these preparations were carried out and the funeral service arranged. This wasn’t just a sign of respect, either — one of the reasons for watching the body was to make sure it didn’t show any lingering signs of life. News stories, even up to the early 20th century, are full of accounts of someone actually regaining consciousness during a funeral service, or of a family member detecting movement during the period of mourning and reviving the fortunate survivor.

Poe’s story, which was at least partly cribbed from an earlier story called The Buried Alive published in an issue of Blackwood‘s magazine of 1821, is only one example of the genre. The Danger of Premature Internment (1816) and Thesaurus Of Horror (1821) both include lurid, terrifying tales of some poor soul trapped in their own coffin, scratching in terror and beating at the wood of the “narrow house” that confines them. Some stories circulated, like modern urban legends, from one generation to the next with only minor changes of location to keep them fresh.

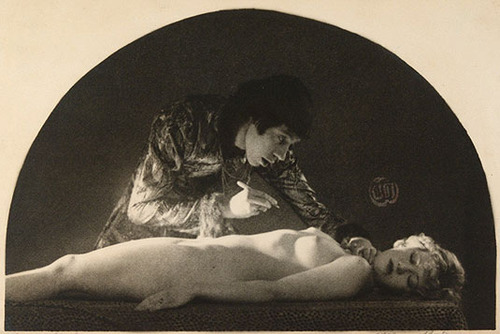

Antoine Wiertz, The Premature Burial, 1854.

In one, a Henry Watt(s) is described as having been saved from his coffin by his own groaning, after it had been nailed up and was ready to be lowered into the grave. The same story was heard in Yorkshire, Surrey, and Oxford (at least) in the late seventeenth…or was it the eighteenth? No, it was certainly the nineteenth century (See, variously, The Yorkshire Wonder: Being a Very True and Strange Revelation How One Mr. Henry Watt Made a Great Noise in A Coffin (1698); The Surrey Wonder: Giving a True And Strange Relation of Mr Henry Watts (London? 1770); The Surprising Wonder of Doctor Watts (1800?)).

Another factor that played into this fear, especially in Europe where burial plots or crypts were often re-used after a few years, involved accounts of disinterred people showing signs of having awoken following burial. Many of these tales certainly belong purely to the realm of folklore, while others likely could be explained by other circumstances. But the myth persisted and the fear of premature burial was very real. It wasn’t until the invention of the stethoscope in 1816 that doctors had access to a marginally more accurate means of determining actual death. The concepts of ‘brain death’ or ‘cellular death’ were far in the future, and it was generally believed that once someone crossed the threshold there was no coming back.

Then, starting in the early 1800s, everything started to change.

Electrifying Experiments

Today, electricity runs the world. In the 18th century, it was little more than a toy. Wealthy men bought or had built crude electrostatic generators, which they used to make party guests’ hair stand on end or shock unwary friends.

Party trick: eighteenth century static electricity experiments.

Electricity quickly became a fad, with people experimenting with its possible uses in all sorts of odd contexts.

A 1753 experiment with static electricity and “electro-horticulture”

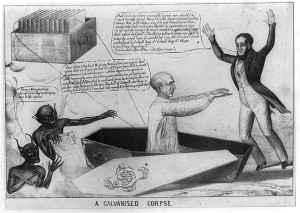

Experimenters also used “Galvanic piles” (today we call them “batteries”) in even stranger displays. In 1803, one Giovanni Aldini obtained the corpse of a recently hanged criminal named Forster. Connecting the contacts of a large battery to the man’s mouth and ear, observers were able to see Forster’s “jaw begin to quiver, the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and the left eye actually opened” (Aldini, An Account of the Late Improvements in Galvanism, London 1803).

Some medical researchers thought it might be possible to use electricity, along with “dextrous management” (whatever that means) to resuscitate the dead — or indeed to put the living into a state of “suspended animation” from which they could be revived. Whether the latter belief was inspired by party tricks gone wrong, with participants knocked senseless by a jolt of electricity and later revived by another, is best left to the reader’s imagination.

Such experiments introduced significant ambiguity into the whole issue of life and death. If a Galvanic pile could cause a corpse to twitch, was the corpse really a corpse? Was it possible to move back and forth across the “threshold” of death, possibly bringing back knowledge of the afterlife? Such uncomfortable questions had probably never been considered outside the realm of religion. Now, it seemed, there might be ways to cheat or toy with death.

Other discoveries were soon to add even more ambiguity to the question, and to put the fear of premature burial into the minds of generations of Europeans and Americans.

Knockout Drops

Prior to 1846, all surgeries were carried out with the patient conscious and writhing in agony, held down by burly surgical assistants while the surgeon sliced off an infected leg or arm. Experienced surgeons could remove a leg, start to finish, in less than a minute (Dr. Joseph Liston, who practiced in the 1840s, is said to have taken as little as 30 seconds on some occasions).

But in 1846, Liston decided to operate on a man named Frederick Churchill after the patient was rendered unconscious using inhaled Ether. A few minutes later, Churchill awoke, looked around, and asked when the operation was going to commence (peals of laughter from the audience…no, really). But because Ether was dangerous and unreliable, other chemicals were tried. In 1847 James Simpson, a professor of midwifery at Edinburgh University spent the better part of a year sniffing, drinking, and otherwise testing every chemical compound he could lay his hands on. One day he woke up on the floor after having inhaled concentrated Chloroform vapors. Anesthesia had arrived.

Anesthesia using Ether

While the use of Chloroform dramatically improved surgical outcomes, it introduced a new problem. Patients were said to be “dead to the world” while under its influence. They felt (or at least remembered) no pain. So what state was the human body in while under its influence? It wasn’t dead since the patient was still breathing, but it didn’t respond to pain while anesthetized.

The discovery that multiple states of awareness existed between consciousness and death added even more complexity to the whole issue. New terms were coined to describe these proposed conditions: “trance,” “syncope,” “coma,” “catalepsy,” “suspended animation,” and “human hibernation” were probably most popular, though others can certainly be added.

The idea that humans might be able to put themselves into a state resembling death (usually known as a trance or suspended animation), while retaining the ability to recover on their own was probably also influenced by other, unrelated discoveries. Europeans were more and more enthralled by the wonders of the Far East, with Indian “fakirs” and ascetic holy men claiming the ability (sometimes tested under allegedly scientific conditions, sometimes blindly accepted) to enter a state in which they required no food, water, or air. This, along with the discovery of various species of frog and toad that can “go dormant” for long periods in order to escape cold or dry spells convinced some researchers that humans might be able to perform similar feats.

Body Snatching

The final component that allowed fears of premature burial to emerge as a near “moral panic” in late Victorian Europe was that of unwanted postmortem dissection or vivisection (accidental or otherwise) by anatomists or surgeons.

Is she dead or alive?

This fear was especially prominent among the poor, who feared doctors would be too badly trained, lazy or otherwise unmotivated to ensure someone was actually dead before pronouncing them as such. Also compare this to modern fears, in areas like South America and Southeast Asia, that rich European or American clients hire doctors to steal organs from poor people. Numerous cases of anatomists buying corpses of recently hanged criminals from professional body snatchers can be found.

In some cases such fears were justified, while in others they were simply an element of fear in the class struggle between the Victorian rich & poor. Elizabeth Hurren’s book Dying for Victorian Medicine: English Anatomy and its Trade in the Dead Poor, c.1834 – 1929 covers the myth and reality of this situation in great detail.

The Stage Is Set

We now have all the elements for a moral panic over premature burial. Medical science has discovered that death may not be absolute, that electricity can be used to “animate” corpses that, therefore, might not be corpses, and that various “not dead but not conscious either” states seem to exist. The looting of corpses from cemeteries is relatively common, not just for use as cadavers but also for petty theft of grave goods. The idea that Grandpa might be disinterred and victimized while still alive is even more horrifying than outright abuse of his corpse.

Into this volatile mix stepped an interesting cast of characters. One of the first, a Dr. Franz Hartmann, published a pamphlet in 1894 entitled Buried Alive: An examination into the occult causes of apparent death, trance and catalepsy. This was mostly a catalog of lurid tales of vivisepulture and its horrors, all undocumented and frequently ridiculous. A reviewer in the British Medical Journal in 1896 lambasted it, noting “what is to be thought of the credibility of an author who gravely narrates a case of an Englishman who died of typhoid fever in 1831, who was buried four days later, and after another four days of burial in a coffin in a grave was exhumed and found alive, and who stated that he had been conscious all the time, and that his lungs had been paralyzed and used no air, and that his heart did not beat?”

The same reviewer also (rightly) ridiculed Dr. Hartmann’s “still more startling statement […] that even putrefaction of the body is not a certain sign that life has entirely departed.” One wonders what signs Dr. Hartmann would accept!

Hartmann’s work was followed by that of William Tebb, Walter Hadwen, and others who founded the London Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial (LAPPB) in 1896. This was not the only such group that was formed during the era, either: similar groups existed in Germany and other countries. According to its charter, the LAPPB’s charter was:

1. The prevention of premature burial generally, and especially amongst the members.

2. The diffusion of knowledge regarding the predisposing causes of the various forms of suspended animation or death-counterfeits.

3. The maintenance in London of a center of information and agitation.

4. According to an arrangement entered into with skilled and experienced medical experts in respect to death verifications, members of the association are guaranteed against premature burial.

Tebb was an archetypical, and extremely active, Victorian reformer. He was (variously) active in the abolitionist movement, an anti vivisectionist, an early anti vaccination crusader, a teetotaler, a vegetarian, in favor of protection for children and animals, and a tireless crusader against premature burial. His LAPPB published a pamphlet called Premature burial, and how it may be prevented, with special reference to trance catalepsy, and other forms of suspended animation in 1905. He and others obsessed with this subject danced on the fringes of numerous controversial practices, effectively acting as anti-establishment gadflies for highly visible causes, no matter how odd or unsupported their positions might be. (One could also say the same about certain modern anti-vaccination groups, but that’s another story).

The Germans created an interesting and possibly unique response to fears of premature internment: “waiting mortuaries” where allegedly deceased individuals could be taken so they could be monitored for signs of life. These first appeared in the 1790s, and were popular throughout the Victorian era before dying out (sorry) in the later 19th century. In these facilities, bodies might be fitted with strings tied to bells that would ring if the corpse-patient (which would it be?) moved. Workers would sit for extended periods, generally among putrefying bodies, watching for movement. One hopes they were really, really well paid for this work.

While the fears generated by such groups were largely imaginary and overstated, Victorian era doctors often had few professional credentials and some may have been incompetent in the area of determining whether a patient had in actuality become a corpse. Groups like the LAPPB and others did have the effect of forcing governments to revise standards in terms of which doctors were permitted to issue death certificates.

The process became easier once improved instrumentation became available, and doctors in the later Victorian era would generally have accurate stethoscopes and opthalmoscopes (the latter used to examine the retina for deterioration) as well as hypodermic syringes to inject a small amount of ammonia under the skin in order to check for an inflammatory response. They might also have a magnesium lamp that would allow them to examine the thin skin between the fingers for signs of circulation (Grave Doubts, Journal of British Studies, Vol 42 No 2, Apr 2003). Such instruments, as well as more stringent training standards, did much to reduce claims of medical incompetence.

Marketing Opportunities

Naturally, all these fears inspired entrepreneurs. Certain types of “patent” coffins were designed to allow accidentally interred victims to activate surface-mounted flags via a long cord. The victim could simply begin pulling the cord to signal their distress to cemetery workers.

Safety Coffin

Those interred in surface crypts could enjoy the protection of special vaults with internally accessible handwheels. Someone awaking in such a chamber could simply turn the wheel to open the crypt from within and escape back to the land of the living.

Some people were so fearful of accidental premature interment that they left specific instructions in their wills to prevent the possibility altogether. One woman instructed her physician to sever the arteries in her neck so completely that no possibility of awaking in her coffin existed, for example.

It was long rumored that certain very wealthy people (Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science movement, is often cited in this myth) had telephones installed in their crypts in order to allow them to call for help if needed. None of these claims are known to have ever been verified, but they make great stories.

In time, still further improvements in the ability to detect signs of life using EEG and ECG machines, as well as additional research into the processes involved in death, would make groups such as the crusading LAPPB and its sister organizations obsolete. Today the debate has receded into subtle and often ridiculously acrimonious arguments over the exact nature of brain death (witness the Terri Schaivo case of 2001-05) and claims of “NDE” (Near Death Experiences) by some patients who claim to have temporarily “crossed over” and returned. Many such claims lie firmly in the area of mysticism and wishful thinking, and are the modern stepchildren of Spiritualist and other movements popular during the Victorian era.

Premature burial fears seem quaint today, and are largely relegated to rural areas in less advanced countries. A century ago, they were very real and very common in the most advanced nations on the planet. Ironically, the rapid advance of scientific understanding had the effect of both creating the panic of the latter Victorian era and ending it.

Leave a Reply